It is well understood that to improve skills practice is required. Athletes at all levels practice regularly, musicians practice, singers practice, you get the idea. As language teachers we plan intentional practice into our lessons everyday so that our students can grow in their language abilities. How can we make it more productive?

Altuwairesh’s (2017) approaches the idea of practice in the language classroom in their article “Deliberate Practice in Second Language Learning: A Concept whose Time has Come”. Altuwairesh cites studies that looked at the practice and expertise level of people who practice a particular skill. The studies looked at musicians, asking them to log how long they practiced as well as the type of practice undertaken: practice versus extensive practice.

Some take aways from the article, based on the studies cited include:

- “Extensive practice one gains in a certain field does not inevitably lead to expert performance.”

- “…diligent and persistent application of the basic principles of deliberate practice …play a crucial role in expert levels of performance.”

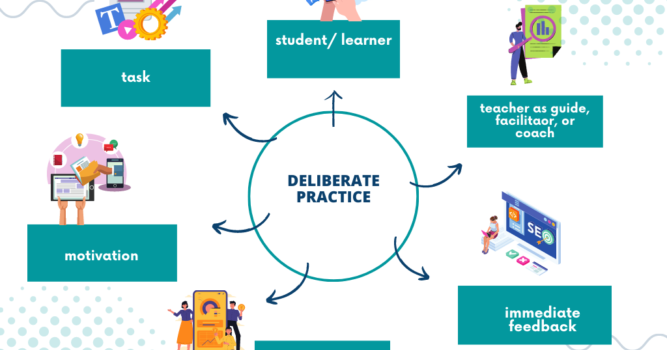

What is deliberate practice? It is “defined as “activities that have been specially designed to improve the current level of performance (Ericsson et al. 1993 as cited in Altuwairesh, 2017). At the centre of this practice is deliberate time for intentional practice. Deliberate practice is also a consistent occurrence, not occasionally; Ericsson suggests daily. This type of practice also focuses on the student, in the case of a language classroom, going beyond their current abilities” (Ericsson et al. 1993, as cited in Altuwairesh, 2017). Ericsson continues to point out that deliberate practice is effortful. This ultimately places demands on the language teacher to prepare practice activities that would be accepted as deliberate practice and that would engage the language student so they put effort into their classroom practice.

How might a language teacher create deliberate practice activities? Planning is at the centre of these types of activities. Teachers should also consider how they will scaffold students, enabling them to enter the activities at a level they feel comfortable and capable in, while guiding them to go beyond their current level of ability. Scheduling intentional activities at regular intervals so that students have multiple opportunities to practice and improve. Regular feedback to students during the activity so they understand what they are doing well and how they might go beyond their current ability. A logical next step to feedback is to discern whether feedback should be formative or summative. The intention of the practice and the amount of practice students have had will help with determining this. Motivation is a common factor in student improvement and one a teacher needs to be aware of. Students must be willing to participate and to work hard at this deliberate practice.

The role of the teacher in deliberate practice is one of coach or facilitator. Teachers set the scene (activity). Deliberate practice is learner-centred and therefore the learner takes on the responsibility for their learning and their improvement. Small groups enable the teacher to circulate and give feedback in the moment.

Different from the rote memorization of years past, deliberate practice offers learners multiple opportunities to practice with effort and concentration while receiving in-the-moment feedback from the teacher who acts as a guide or coach. Setting classroom activities and schedules to include such practice will enable learners to continually improve their level of language ability.

Here are some other resources on deliberate practice:

Altuwairesh, N. (2017). Deliberate Practice in Second Language Learning: A Concept whose Time has Come. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 4, 111-115.

Baron, R. & Henry, R. (2010). How entrepreneurs acquire the capacity to excel: insights from research on expert performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4, 49-65.

Eliason, N. (2017, July 3). How to use Deliberate Practice to reach the Top 1% of Your Field. Website. https://www.nateliason.com/blog/deliberate-practice

Ericsson, K. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert performance. Psychological Review, 100, 363-406.

Lawless, L. (2023). Deliberate French Practice. Website. https://progress.lawlessfrench.com/learn/deliberate-practice?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=lawless-french-deliberate-practice-elisions-leurrer-mot-du-jour-3972